This story was originally published in the Winter/Spring 2023 issue of Appalachia Journal.

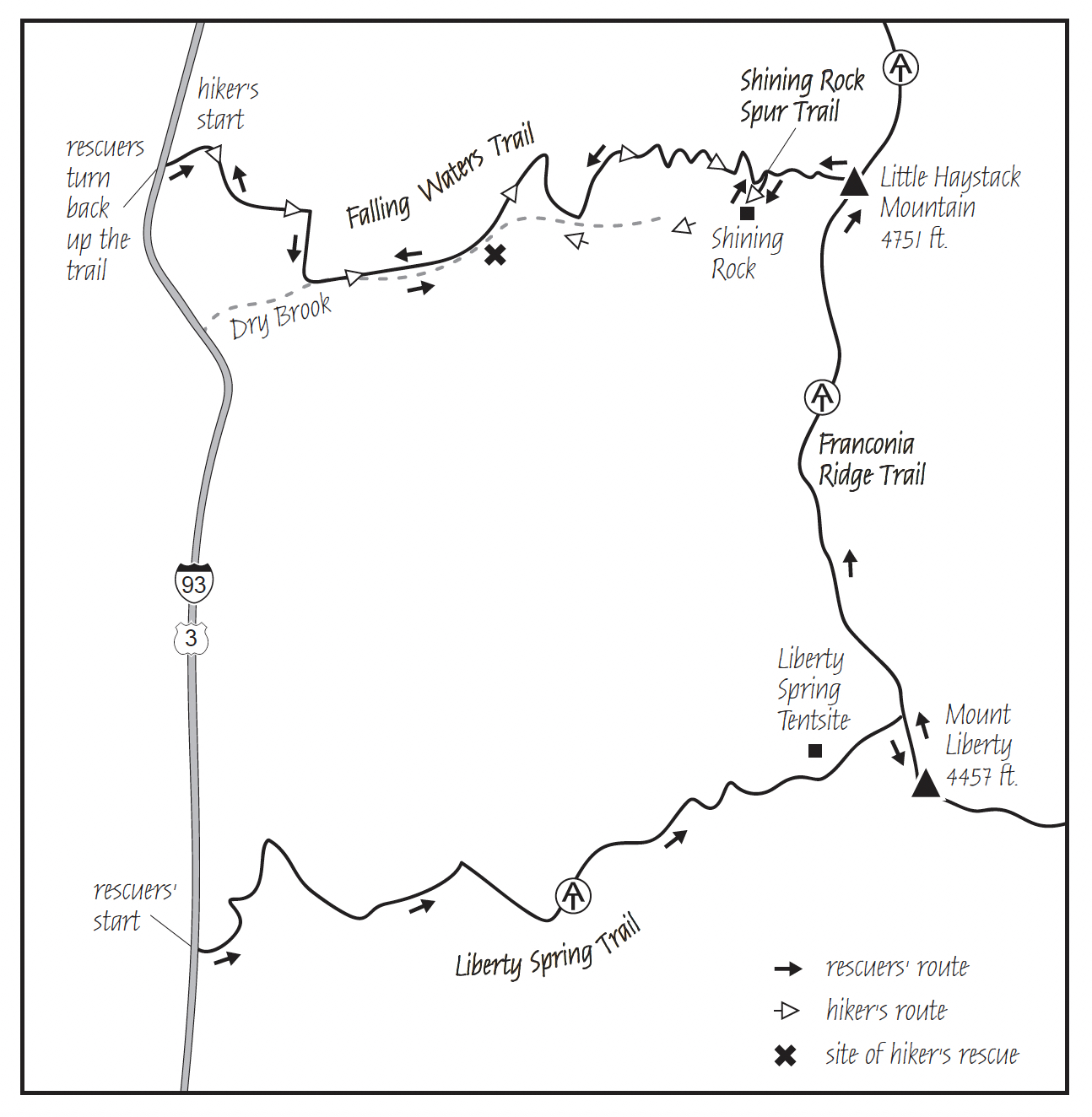

The route of the Upper Valley Wilderness Response Team as it searched New Hampshire’s Franconia Ridge area for a missing 60-year-old hiker in early May 2009.

On a chilly night in early May 2009, the pager sounded. New Hampshire Fish and Game (NHFG) summoned our Upper Valley Wilderness Response Team (UVWRT) to assist with a search. A man in his 60s was missing on or around Franconia Ridge in the White Mountains. NHFG officers and two other rescue teams had already searched the steep area without finding him or identifying any clues that might lead to refining their search strategy.

We were asked to stage at the trailhead to Falling Waters Trail by 8 the next morning. It would be day four. The hiker had already been out three freezing nights in knee-high snow with little extra clothing or gear. According to his family, this was his first mountain hike in more than 20 years.

While we geared up at the trailhead, Scott Carpenter, our team leader, approached me with map in hand to detail my assigned task. I continued to tighten my boots and attach my gaiters as he spoke. He requested that I take our new team member, my longtime friend, Tom Frawley, to conduct a “hasty search” of several major trails on the western flank of the north–south ridge. We were to ascend the Liberty Spring Trail for 2.9 miles to Franconia Ridge, then proceed north 1.9 miles along the exposed Franconia Ridge Trail before descending 3 miles on the Falling Waters Trail back to Route 3. I thought, Wow—this is a long and involved search request— but just the challenge I was hoping for, considering others were searching areas along the highway.

Tom and I anxiously reviewed our mental checklists. We added gear we’d need above treeline to our packs. Lieutenant Todd Bogardus of NHFG called us to his pickup truck for a briefing. Twenty-five searchers, mostly geared up and ready to go, gathered in a semicircle around the open tailgate waiting to hear a search update and description of the missing man. I pulled a small notepad from my radio harness and began writing—subject’s name, age (63), height (5 feet, 8 inches), and weight (250 pounds), no known trip itinerary. When a teammate questioned the lieutenant about any medical conditions, we learned that he was diabetic, on medication for high blood pressure, and had arthritis in his knees. This certainly did not fit our typical missing hiker profile. Yet, his car was right here, 30 feet away, and he was out there, somewhere in the vast wilderness, likely desperate for help.

Bogardus had also just deployed 30 other searchers and 6 air-scent dog teams to comb river drainages, trails, and low-lying areas, suspecting that our subject had traveled downhill. Clearly, our search assignment was just one piece of many that were attempting to solve the master search puzzle.

Only a few snowbanks remained in the warming valley, but we expected snow and ice higher on the mountain. Eager to get going, Tom and I quizzed each other—did we have a stove, shelter, crampons, bivouac sacks, headlamps, and so on—before shouldering our 30-pound backpacks and heading up the trail. We were prepared, equipped with enough food and gear to spend the freezing night out if necessary.

This was my chance to break Tom in right, putting into action the best-practice search tactics and strategies that I had been teaching as training officer for UVWRT. As we approached the trail, I emphasized that we were on duty now, and our mission required total focus; there would be no chatting about last night’s ball game, work, or the kids. We had an important job to do. Tom and I had hiked and climbed together for many years and volunteered as emergency medical technicians on our small-town rescue squad. This was Tom’s first UVWRT callout, and we were absolutely committed to following search protocol, knowing a man’s life could hang in the balance.

We reset our GPS units to record our tracks and set a waypoint marking our coordinates, before heading up Liberty Spring Trail. We had nearly ten miles of challenging terrain to search before dark. At first, we made quick progress, scouring the trail’s flanks, one focused on the left side, and the other searching the right, looking for a track or clue, something out of place—a man who had already been out three cold nights without proper clothing, gear, or shelter. Since the deciduous leaves had not yet emerged, we had good visibility, allowing us to scan broadly into the open hardwood forest. This would change as we gained elevation and entered dense coniferous stands of spruce and fir, which would make visual detection more difficult. Of course, lots of possibilities ran through my mind. Given our subject’s medical condition, lack of experience and fitness, combined with three frigid nights out in the elements, we knew this could become a body-recovery operation. We also knew all search situations require an absolute positive “I will find him” attitude.

Former New Hampshire Fish and Game Lt. Todd Bogardus at the site where the lost hiker improvised a shelter from spruce bows to survive the frigid temperatures.

The “hasty search” is sometimes referred to as “running trails,” but that’s certainly not the reality. If you’ve run trails before, you know that it’s hard enough to just place your feet, avoiding slippery roots and rocks. At a jogging pace, it would be impossible to visually inspect both sides of the trail and to look for clues, all at the same time. Finding a credible clue, like an article of clothing, a gum wrapper, or a footprint veering off the trail into the woods can be critical to closing in on a “find.” The hasty search is a means of quickly, but methodically, checking highest probability areas first—established trails, campsites, structures, and other points of interest.

Searchers use sound attraction as an effective way to locate a conscious and responsive victim. Frequent whistle blasts along the trail can penetrate the darkness, fog, or the thickest stand of evergreens, to quickly capture the attention of a disoriented subject. Typically, we blow the whistle one long loud blast, followed by yelling the missing person’s name. We then listen intently for a response. This requires a real whistle, not the little toy toot-toot built into the sternum strap of many packs. In my experience, this “whistle blast” strategy has often resulted in a jubilant cry—“Over here! Help! Over here!”

Tom and I steadily climbed the long steep section of the trail, which here coincides with the heavily tracked Appalachian Trail, to the Liberty Spring Tentsite, where the mudand branch-littered snow measured well over a foot deep. We spent about fifteen minutes there—just enough time to snack, hydrate, and check the maze of side paths to various tent platforms—but found no evidence. I recall noticing a Canada jay perched only six feet above on a spruce branch, ready to snag any crumb we might leave behind.

We continued up to the 4,200-foot north–south Franconia Ridge Trail, finding that the uphill walking was tricky, requiring balancing precariously on a narrow monorail of hard-packed ice and snow. Sometimes, teetering under our pack load, we would slip off the frozen consolidated middle and posthole into the loose granular snow on one side or the other. From the ridge trail junction, I radioed to search command, “Would you like us to detour to check the trail south to the summit of Mount Liberty?” After a short pause, the lieutenant’s voice crackled over the radio, “Affirmative.” So, we headed south, less than half a mile, down into the wooded col and then scrambled up to the boulder-strewn peak for a look around, finding no sign of anyone. This extra leg south added considerable time to our already arduous assignment, but we felt that “clearing” that area was worth the time and effort. I wondered if the missing hiker had any hiking essentials with him: map, compass, matches, or a whistle. Maybe he knew that three blasts of a whistle signal a distress call for help. We continued to scan the trail for any suspicious track veering off.

Soon we were back at the junction, heading north up the exposed ridge toward the Falling Waters Trail almost two miles away. Aside from a few drifts, little snow had accumulated on the windswept ridge, but thick passing clouds and gusting squalls of snow and sleet hampered our progress. We appreciated our previous stop below treeline to put on a windproof shell layer of protection. Forging ahead, we continued our northern trek along the slender curving spine of ice-glazed rock, often venturing off the trail to look behind rock outcrops and in sheltered crevices, hoping to find our subject taking refuge, calling his name—still no response.

As we neared the 4,751-foot summit of Little Haystack, two faint figures emerged from the swirling whiteout, walking slowly toward us. We waited a minute, wanting to engage the pair of southbound hikers. Huddling close enough to be heard over the raging wind, we told them about our search. “Have you seen anyone?” Answering in a deep French accent, the two Canadian men assured us they had not seen our missing hiker. They asked for directions, unsure of their exact location. We took a minute to orient them. Then we parted ways, heading west, down our last three-mile leg, the Falling Waters Trail. Descending the steep spruce-lined path sheltered us from the 18-degree Fahrenheit windchill. Grateful for our crampons underfoot, we confidently navigated the slick path of snow and ice down to the Shining Rock Spur Trail. We stopped to shed our wind gear, take in some calories and drink water. Again, we radioed NHFG command to update our progress, and to request a short side jaunt to check the popular hiking destination, Shining Rock, an impressive ice-covered granite face. We got the go-ahead.

Tom waited at the trail junction, while I scooted down the short side path to Shining Rock, which was not glistening in the sun that day but obscured by dense cloud cover. I surveyed the small heavily tracked area, which was bordered by the ice-covered rock face on the high side and a thick hedgerow of evergreens on the low side. Corralled inside I found a hodgepodge of indistinguishable tracks and postholes penetrating the old snow. There was no obvious clue leading to our subject, but I took a quick look around, and called out his name before heading back to Tom. Together, we continued down the Falling Waters Trail, systematically looking, whistling and calling out—in vain, it seemed by now.

Finally, after a long traverse in thinning snow, we arrived at Dry Brook, a crystal-clear shallow mountain stream, which was not dry, but flowing swiftly over rocky falls and around moss-covered boulders. The noise of this rushing spring runoff overpowered our blasts and shouts, which we continued more often now to compensate for the river’s rivalry. From there, the trail dropped steadily down the steep drainage. We crossed the swollen brook several times, hopping from rock to rock, before finally arriving at the trailhead around 5 p.m.

It had been a long and taxing day. We were the last team to return— relieved to remove our heavy backpacks and grab some food. Our lengthy search assignment had been completed, but sadly, there was still no sign of our subject, and darkness was closing in. Another 30-degree night was in the forecast. I couldn’t stop thinking about our cold missing 63-year-old and his family; the weight of this difficult loss exhausted me even more.

Dutifully, we reported to search command, where Lt. Bogardus downloaded our GPS tracks onto the master laptop. As he did, we could clearly see a myriad of red squiggly lines crisscrossing brooks, trails, roads, and contour lines, delineating the hundreds of total miles searched in the last 32 hours. As expected, we learned that the search effort would be ended for the day.

At that very moment, to our amazement, a hiker came running down the trail, bursting into the parking lot—shouting, “We found him, we found him!” Right away I realized that it was one of the Canadians Tom and I had helped orient high on the inclement Franconia Ridge, 3,000 vertical feet above. They must have followed us down and—somehow—they had found our subject.

A more recent photo of Jim Mason on the summit of Little Haystack, where he and Tom met the two Canadian southbound hikers that stormy day.

They told us that our hiker was alive. The pair of Canadians had split up after they encountered him. One was with him now. They had found him creeping up the snow-splotched slope from the brook toward the Falling Waters Trail, the very trail we just descended. How could we have missed him? We needed to get back up the trail quickly; it would be dark soon. Within minutes, I had strapped our two-piece titanium litter onto my pack, while Tom and about eight teammates divvied up the remaining gear. Along with a dozen NHFG officers, we all headed back up the mountain with a renewed sense of urgency—and for me, a huge feeling of relief.

Nearly 1.6 miles up the Falling Waters Trail, not far from Dry Brook, we found a wet, cold, and lethargic man with bare, freezing feet. He was conscious, but not alert. I took a minute to catch my breath and remove my pack. Arriving teammates assembled the litter, while I assisted the NHFG medic, who was assessing our patient and checking his vital signs. Using trauma shears, I snipped away his water-soaked cotton sweatshirt. His dank skin, now exposed to the air, allowed the moisture, like rising steam, to evaporate from his hefty torso. We placed heat packs inside a sleeping bag, then hypowrapped him in a tarp like a burrito to retain heat and secured him to the litter for the long, rough carryout. Without delay, we needed to get this helpless, hypothermic, and frostbitten man safely down the mountain.

We knew the first half-mile of trail along the brook drainage was steep, wet, and slippery, making the descent risky. Tom and I went down ahead of the litter, equipped with a rope, slings, and carabiners to set up a safety belay line, which we anchored to trees above the first long exposed section where a slip or fall could be disastrous. We clipped the rope into the litter as the carry team squeezed by us, and right away I felt the load tension our belay. We fed out the rope as they progressed, prepared to lock off the static line, should there be a sudden mishap. By radio, we warned the litter team when only 30 feet of rope remained, giving them time to find a safe spot to stop, set the litter down, and rotate out to a fresh team of six carriers, three on each side. Other times, all twenty rescuers flanked the trail and passed hand-over-hand, person-to-person, the 250-plus pound litter down the less precipitous rocky sections. Running mainly on adrenaline, I was reminded how strenuous and demanding rescue operations can be. We were all eager to get our victim down, warmed up, and transported to the hospital by the waiting ambulance. Guided by headlamps, we still had to navigate two frigid brook crossings.

At 8:20 p.m., as our patient was being moved from the litter onto the stretcher and loaded into the ambulance, I asked him, “What happened?” He whispered, “I heard a whistle and went toward it.” Obviously, motivated by hearing our calls, he had mustered enough strength to crawl on hands and knees through patches of snow and across the narrow, freezing stream to get to the trail where, just by luck, the two Canadian hikers were descending, not far behind Tom and me.

We later learned at an incident debriefing that on the day following the rescue, Lt. Bogardus and Conservation Officer James Kneeland had gone back up the trail to the location where the man had been found. They backtracked his footsteps to find where he had constructed nests of insulating evergreen bows and burrowed in for three cold lonely days and nights. Strewn around his improvised life-saving den they found remnants of snack food, a small day pack, and a few articles of discarded soaking-wet clothing.

Continuing up the slope, Lt. Bogardus and CO Kneeland followed his barefooted tracks in the snow right to Shining Rock. Remember the corral of tracks and postholes I had observed below the icy face? He had been there! His tracks were proof that he had been there—evidently, he had forced his way through the thick spruce border on the low side, then gravity helped to pull him down into the steep, snow-filled gully below.

I asked myself, How did I miss his tracks? If I only had taken more time to “sign cut” that area—search outside the dense evergreen thicket—I would have found his lone track of desperation heading down the gully. At the bottom of one posthole in thigh-deep snow, the officers found his black Velcrostrapped sneaker still wedged deep in place. What a struggle this man must have endured as his predicament unraveled! My failure to thoroughly inspect the area below Shining Rock could have cost this man his life. Checking the outside perimeter of such highly tracked areas can lead to a footprint or a clue, which in this case would have led us right to his isolated dens of survival—and beyond, to our subject, a man in desperate need of help. Surely, he hadn’t intended for his short day hike to become a four-day ordeal—a struggle to stay alive.

In the end, you could say our subject was saved by the whistle, his own determination, and good luck. Sound attraction worked. Our persistent whistle blasts and calling out paid off—attracting him to the trail, where he was found—wet, cold, and unable to walk—by the last passersby of the day.

If you enjoyed this story, you might consider subscribing to our Appalachia Journal.